Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio?

The feminization of politics and culture is destroying both.

I was writing a personal note to a friend recently and in commenting on current events I shared my opinion that most of the problems we’re experiencing across the western world are a direct consequence of the feminization of our politics and culture.

I told her—dishonestly, it turns out—that this was something I could never write about on my blog or my Substack because it was the kind of thing that could be all too easily (and in many cases all too willfully) be misunderstood.

“Oh, he’s a misogynist,” people would say. And they’d have the excuse they needed to ignore or dismiss anything I say—ironically enough, because of the very feminization of our culture.

I’m not being critical of women, nor am I being critical of femininity. I’m merely concerned, as I said, about the feminization of things. If my saying so makes someone feel slighty or angry or “marginalized,” however, then it’s somehow proof that I’m wrong.

It’s not a very good game.

People may not like that I’m equating femininity with (among other things) a tendency to indulge the emotions, in contrast to masculinity’s typical association with their suppression. I’m not suggesting that all women are hysterics or that all men are stoic. Far from it. I’m acknowledging that every human being is a blend of emotion and reason. If men couldn’t be “feminine” in this sense, then there’d be nothing to worry about.

The difference between femininity and masculinity goes deeper than the mere indulgence or suppression of emotion, obviously. The masculine virtues tend toward independence, stoicism, resourcefulness, perseverance, persistence, aggression. The feminine virtues tend more toward community, sacrifice, compassion, tenderness, gentility, accommodation. These virtues can be found to a greater or lesser extent in everyone, male or female (or, these days, whatever), and they’re often intertwined.

I’m going to continue using the masculine and feminine model, but if you find that off-putting substitute “hard” for masculine and “soft” for feminine. Hard virtues and soft virtues. Knock yourself out.

The problem, as I was saying, is that we seem to have conflated the need to allow women more involvement in our politics and culture with the need for a more feminine politics and culture. By the same token, we seem to be equating maleness with masculinity, which is just as wrong.

We hear a lot about masculine toxicity, never a word about feminine toxicity. That in itself is food for thought.

It’s a positive thing to have women voting and holding office and running corporations, but in moving toward their greater involvement we seem to have made the erroneous assumption that the original problem wasn’t the lack of female representation in our legislatures and boardrooms, but rather the lack of femininity.

That’s where we screwed up. That’s the thing we got wrong.

Our politics and culture have consequently become too emotional, too accommodating, too nurturing. Above all, too indulgent.

There’s the old canard that hard times make hard men, hard men make good times, good times make soft men, and soft men make hard times. In Book V of The Republic, for example, Plato calls for women to share the duties of the state:

Then let the wives of our guardians strip, for their virtue will be their robe, and let them share in the toils of war and the defense of their country; only in the distribution of labors the lighter are to be assigned to women, who are the weaker nature, but in other respects their duties are to be the same. And as for the man who laughs at naked women exercising their bodies from the best of motives, in his laughter he is plucking “a fruit of unripe wisdom,” and he himself is ignorant of what he is laughing at, or what he is about; —for that is, and ever will be, the best of sayings, That the useful is the noble and the hurtful is the base.

Plato isn’t calling for the feminization of his Republic, but for the inclusion of women in its masculine offices. The “toils of war and defense of their country” require the masculine virtues of discipline, aggression, courage, and even ferocity. Plato acknowledges that women are physically weaker than men and makes the necessary allowances, but he’s making the obvious point that women can and should contribute to the common welfare—and that in doing so they should adopt the masculine virtues rather than feminize the institutions.

Plato’s reference to the toils of war is significant. Historically speaking, war has been the great recurring crisis to plague the human race: the whetstone on which we have sharpened and polished our civilizations.

Not the only crisis, but the most frequently recurring one.

In a letter to his wife Anna, Fyodor Dostoyevsky wrote that “Without war human beings stagnate in comfort and affluence and lose the capacity for great thoughts and feelings, they become cynical and subside into barbarism.”

He was echoing something Thucydides had written a few thousand years earlier in his History of the Peloponnesian War: “. . . war is a stern teacher; in depriving them of the power of easily satisfying their daily wants, it brings most people’s minds down to the level of their actual circumstances.”

In today’s more vulgar lexicon, we might say, “in wartime shit gets real.”

Neither Dostoyevsky nor Thucydides was praising war per se: they were praising one of the collateral consequences of war. More accurately, the consequences of the crisis of war.

Ukrainians aren’t arguing about pronouns, gender, or the sins of their country’s past. They’re much too busy just trying to survive. A Ukrainian seeking a “safe space” isn’t looking for a place where no one disagrees with him, but somewhere he won’t be blown up or shot. That’s obviously not a desirable state of affairs, but it is a state of affairs, and such conditions are a purifying fire that burns away all that is superfluous and supercilious.

And the need for “safety” from ideas one finds disagreeable is certainly superfluous.

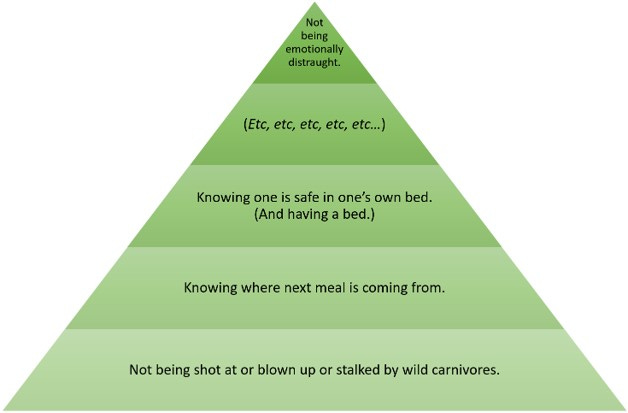

I can illustrate what I mean about with a couple of graphics.

There are certainly social questions worthy of debate that get pushed aside in times of crisis. I’m not suggesting that complex cultural conversations are stupid or irrelevant (though god knows I certainly feel that a lot of them are). I’m merely saying our priorities are out of line.

When in times of peace and prosperity we allow those social questions to displace the more existential questions of how best to maintain our peace and prosperity, we run the risk of losing both. Since war and want will inevitably render those social questions irrelevant, anyone genuinely interested in them would do well not to lose sight of their secondary nature and significance.

That is: if you think your country needs a “national conversation” on gender or race or sexuality, then you have to understand that your country’s liberty and prosperity are the prerequisites for that conversation to take place.

Everyone’s familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: I’ll use a variant of that model to illustrate my point more plainly:

A culture in genuine crisis doesn’t have the luxury of indulging the kinds of baroque questions that are dominating a lot of western culture right now. It’s wonderful to have that luxury, it’s wonderful that I myself can write these words at my leisure instead of wondering how to feed my family or evade a deadly enemy or not freeze to death, but we have to remember that it is indeed a luxury. It is not the natural order of things. There are billions of people alive today who would gladly trade their existential problems for your emotional discontent.

Today’s westerners can argue about gender and pronouns and immigration and the sins of our forefathers only because our forefathers bequeathed us the peace and prosperity necessary to have such arguments in the first place. The minute we lose our peace and prosperity no one’s going to care about any of those things.

The feminization of our politics and culture—or, if you prefer, the emasculation of our politics and culture, which amounts to the same thing—almost guarantees we will lose our hard-won peace and prosperity.

The most corrosive aspect of this feminization or emasculation is the elevation of emotion over reason.

Think how often you’re asked to consider how something makes other people feel. An emotionally healthy person should certain be compassionate and considerate of his fellow man, but we’ve gone well beyond that. An entire emotional vocabulary has infected our language to such an extent that phrases like these are now considered logical arguments worthy of consideration:

“That’s invalidating my existence.”

“This is the truth of my lived experience.”

“You’re denying my personhood.”

“Your words are violence.”

“Your arguments make me feel unsafe.”

And, of course, most poisonous of all is the very idea—now considered an inviolable truth—that one’s skin color, sex, ethnicity, sexuality, or religion determines the relevance and validity of one’s arguments. That idea has no basis in actual reason.

In formal debate, a contention is an idea or a point for which a person argues by means of empirical evidence and logic.

Using emotion to argue against facts and logic can be a very effective means of building support, it can be quite persuasive, but it’s not productive because it’s not real. The efficacy of any given policy has nothing to do with how anyone feels about it but with whether it’s likely to solve the specific problem it proposes to address.

In our feminized culture, however, social arguments are routinely fought and won not on the basis of facts and logic, but how people feel. This state of affairs has been been decades in the making—remember Cindy Sheehan, the distraught mother of a young man killed in Iraq while serving his country? New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd, who opposed the war, declared that the grieving Cindy Sheehan, who had lost her son in the Iraq war, had an “absolute moral authority” that meant that her social, political, and opinions were immune from criticism or debate.

When the rules of the game specify that in any conflict of fact and emotions, it’s emotions that win, you’re going to get more emotion. And that’s exactly what we’ve been getting.

Now we’re literally rewriting history and literature to avoid offending anyone. Public health information is communicated obliquely to avoid “stigmatizing” the very people whose health is most at risk. We celebrate obesity because to address it head-on as a health issue would be “fat-shaming.” Questioning a stroke-victim’s ability to carry out the duties of one of the most important offices in the land is “ableism.” We’re being asked to deny biological reality because a tiny handful of people find the male-female duality of mammalian biology oppressive. We exhaust ourselves in arguments about symbols like flags and anthems because we’ve lost the capacity to discuss the underlying realities rationally. Teacher and professors across America are actually arguing that rationality itself—logic, mathematics, science—is some kind of artificial construct designed to perpetuate white supremacy.

How can you argue rationally with people who don’t acknowledge reason? Who in fact reject it as insufficiently inclusive of their feelings?

Is it wise for women to skip breast and ovarian cancer screenings because they “feel” like men? For men to skip testicular and prostate screenings because they “feel” like women?

How are we supposed to respond to people who entered into voluntary contractual agreements to borrow money but now “feel” it’s hard on them financially to pay it back and that they therefore shouldn’t have to?

Soft people are charting a course for hard times—and doing their best to purge the culture of the hard people that will be so necessary when we get there.

The feminization of our society—the supremacy of feelings and the indulgence of the nurturing impulse—has been facilitated largely by our rejection of the formal value systems that used to provide guardrails against the elevation of our individual emotions over all else.

All the way back in 1943, C.S. Lewis observed in The Abolition of Man:

…those who stand outside all judgements of value cannot have any ground for preferring one of their own impulses to another except the emotional strength of that impulse. . . . It is from heredity, digestion, the weather, and the association of ideas, that the motives. . . will spring.

Indeed.

Spot. On.